Akhenaten is probably the most interesting of Egyptian pharoahs. He was strange in a number of ways, an oddity that upsets the normal course of Ancient Egyptian history and gives rise to theories that are still being argued about amongst archaeologists. It is not for me to enter this great debate; I merely suggest a scenario that fits as well as any other to the known facts.

Akhenaten’s reign (about 1353 BC - 1336 BC) was a hiccup in the great tradition of the pharoahs. For centuries before and after him, little changed in the style of Egyptian art and their beliefs; tradition dictated and the pharoahs followed. Only Akhenaten dared to be different. In his reign art became suddenly more realistic and family-centered. The stiff and formalized depictions that we are so used to in Egyptian art loosened up and we are allowed a glimpse into a more human and natural world.

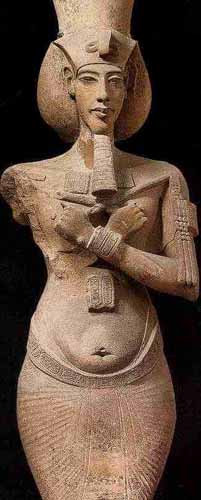

It is for this reason that we can be fairly certain that the pharoah and his wife, Nefertiti, are accurately portrayed by their artists. And Akhenaton looked weird, to say the least. His body was pear-shaped and his limbs thin and elongated; his face too was long and narrow. There has been much speculation on the cause of these apparent deformities, most settling for Marfan’s Syndrome, a genetic disorder that fits closely with what we observe.

Yet there is something very noble and intelligent in the features portrayed in the statue above. And this fits very well with Akhenaten’s attempt to turn Egypt from its old gods to accept a form of monotheism. This began as an elevation of the sun god, Aten, to pre-eminence and developed into a genuine assertion of there being one god only. It is as if Akhenaten was groping towards an understanding that was later to emerge in the great monotheist religions of today.

Again, historians are still debating whether this was a personal aberration of Akhenaten’s or whether he was influenced by outside forces, perhaps the result of his ancestry being riddled with Mitannic princesses. The Mitanni were a people of northern Mesopotamia and it is possible that their rulers practised a type of monotheism.

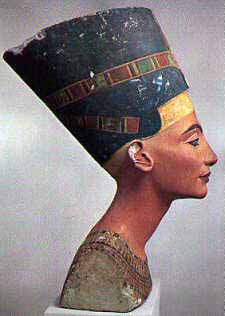

This is where Akhenaten’s wife, Nefertiti, may enter the equation, for she is reputed to have Mitannic ancestry too. Indeed, she supported and encouraged Akhenaten’s reforms and may well have continued them beyond his death. One begins to suspect that we have a true ancient love story here, a romance evidenced by the softening of art forms and the joint effort to change the religion of Egypt. They stood together against the might of Egyptian tradition.

Nefertiti was very beautiful, if this famous bust of her is true to life. It is easy to imagine that Akhenaten was in love with her and that they developed his reforms together. For the brief period of Akhenaten’s reign, a mere seventeen years, they must have discussed and enlarged upon their ideas, always conscious that they were opposed by the establishment, the priests and nobility who depended upon the status quo for their existence both in this world and the next. Their determination speaks aloud of their reliance upon each other, suggesting much more than the usual formal relationship between pharoah and queen.

After Akhenaten’s death, history becomes vague and confusing. A succession of pharoah’s followed, culminating in the boy king, Tutankhamun, who may have been related to Akhenaten. All turned against the new religion however, expunging any mention of it and Akhenaten himself from inscriptions and official documents. Egypt went back to being what it had always been and memory of Akhenaten’s revolution in thought faded into the sands of time.

Yet a faint whisper is left to us. Over the thousands of years comes the suggestion of a human story that is exceptional amongst the formalized accounts of other pharoahs’ greatness and achievements. It is entirely appropriate that we should view the tale of Akhenaten and the beautiful Nefertiti as one of the great romances of history.

.jpg)